(RNS) — Growing up, Jared Garrett never understood the point of his family’s religion.

There was something about Jesus and the end of the world and about always obeying church leaders.

At some point, he got baptized in a kiddie pool.

None of it made any sense to him.

By the time he was 17, Garrett had had enough. He packed his bags and, like many Americans, parted ways with his childhood religion.

According to data from the Pew Research Center, about 4 in 10 (42%) of Americans have switched faiths at some point. Some leave the faith they were raised in, converted by new ideas, hope for a new life, by marriage or geographic relocation. Some swear off faith altogether or find a spiritual path of their own making.

Jared Garrett. Courtesy photo

As it happens, the small, nomadic apocalyptic sect that Garrett grew up in eventually gave up its original mission. Founded by ex-Scientologists turned Satanists, the Foundation Faith of God and its members awaited the end of the world but when it didn’t come, the group decided to rescue animals instead.

It was Garrett, now 46, who ended up finding faith again.

Today he is a father of seven and volunteer pastor, or bishop, of a local congregation of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. He recounts his journey in a podcast called “Tales From a Cult Insider,” where he details his time with the sect and his family’s spiritual history.

The Process Church of the Final Judgment, as the Foundation Faith of God was originally known, got its start in London, where its founders, a couple named Mary Ann MacLean and Robert de Grimston, ran classes offering “compulsions analysis” — their take on Scientology’s practice of auditing — and operated a coffeehouse known as Satan’s Cavern. They befriended celebrities including the musician George Clinton, according to “Sympathy for the Devil?,” a 2016 documentary about the group’s early years.

“As far as I could tell, it was Scientology thrown in the mixer with some paganism and some end-times Christianity,” said Garrett.

The group venerated Jehovah, Lucifer, Jesus and Satan, and was known for dressing in long black capes. Its logo — four Ps, each radiating from the center — closely resembled a swastika.

After being accused of brainwashing its members, about 30 sect members — and six German shepherds — left England, traveling first to the Bahamas and later to a remote Mexican village.

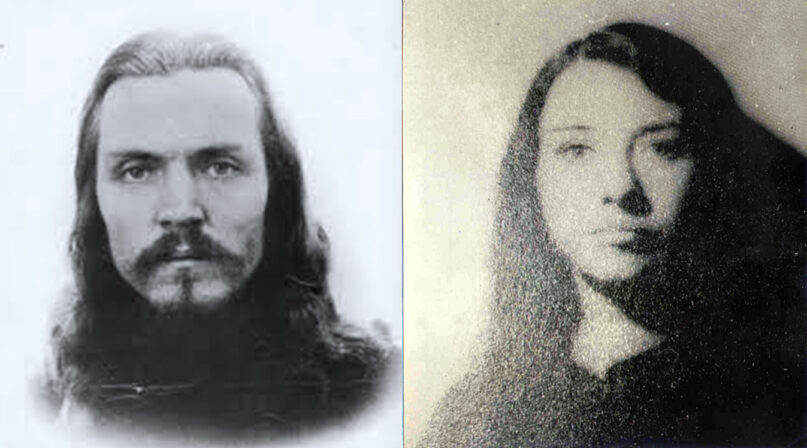

Robert de Grimston in an undated photo and The Process Church logo.

RELATED: Tom Brady, Alex Guerrero and Apocalypse Meow — when weird belief turns harmful

The sect eventually settled in the United States, setting up branches in Boston, Los Angeles, New Orleans, Dallas, Chicago and other cities, and growing to about 150 people.

Jared’s father, Bruce Garrett, now in his early 70s, joined the Process Church while serving in the National Guard near Boston. The year was 1970. There was turmoil in the streets and young people were demanding change, Bruce Garrett said. Many had lost faith in traditional religion.

New religious groups were popping up all over.

The Process Church offered spiritual enlightenment and a warning about the state of the world. One of its main teachings was that human beings had chosen evil over good. Its leaders, harboring little hope that humans could mend their ways, said the only way forward was to withdraw from society and seek spiritual enlightenment while waiting for the world to burn.

“Humanity chose the easy way that leads to Hell, and now its journey is ended,” de Grimston wrote in an essay titled “Humanity is the Devil.”

Robert de Grimston and Mary Ann MacLean in undated photos.

A place to belong

Bruce Garrett met Process members in Harvard Square, in Cambridge, Massachusetts. He had grown up with what he called “not the greatest of family lives,” he said. The Process welcomed him with open arms.

“It was like a substitute for home,” he said.

When he first joined, Bruce Garrett said, men and women lived separately and were expected to be celibate. Since most were in their early 20s, that didn’t work out; when children were born, parents weren’t allowed to raise them, as families were seen as obsolete.

Sect leaders believed breaking families up was the ethical thing to do. Garrett said he followed their teaching, which he now regrets.

“These kids were subject to people who said, ‘You’re not my kid and I really don’t care about you that much,’” he said. “That was unfortunate.”

In “Love, Sex, Fear, Death: The Inside Story of the Process Church of the Final Judgment,” an account of the sect’s early days, Process member Kathe McCaffrey described the group’s rules for families as “arbitrary, harsh, and sometimes plain mean.”

Jan Palombo, a longtime associate of the Process, told filmmaker Neil Edwards in “Sympathy for the Devil?” that the group’s approach to parenting always puzzled her. “They treated the dogs very well. They did not treat the children well.”

Jared Garrett, far left, as a child. Courtesy photo

Growing up, Jared Garrett said, kids got food and shelter, but little kindness or love. For the most part, they were treated as inconvenient, especially by the group’s leaders.

“I have been overlooked by these people all my life,” he told Religion News Service. “I almost felt like I was the enemy.”

Benjamin Zeller, associate professor of religion at Lake Forest College, has heard similar sentiments from people who grew in new religious movements, especially those that have a “world-transforming agenda.” Saving the world, he said, is a lot more exciting work than the messiness of raising a family.

Ironically, new religious movements often attract members by offering a loving community, Zeller said. But members are often so focused on their own spiritual development that they fail to pass that love and care on.

He pointed to the gurukula schools run by the Hare Krishna movement in the 1970s and the 1980s. While parents were out trying to fulfill their mission, kids felt cut off and abandoned and at times were neglected.

“You want to save the world,” he said. “Great. Don’t have kids.”

Rescuing pets

“Sympathy for the Devil: The Story of the Process Church of the Final Judgment’’ poster. Courtesy image

By the time Jared was born in 1974, the Process Church had begun to schism. MacLean and de Grimston divorced and de Grimston departed with a few followers. Those who remained gave up on Satan and occult imagery, though they remained convinced the end of the world was near. Some reclaimed their Christian roots.

“We tried born-again Christianity for a little while,” Bruce Garrett said. “Then we tried just regular Christianity. Then we got to the point where, I guess, we’re just doing our own things.”

The group renamed itself the Foundation Faith of the Millennium and, later, the Foundation Faith of God.

The members eventually grew tired of religion altogether and in the mid-1980s founded what is now the Best Friends Animal Society, based in Kanab, Utah. One of the leading animal rescue groups in the country, Best Friends has spent decades promoting the no-kill shelter movement.

The group now cares for about 1,600 animals and facilitated nearly 27, 000 pet adoptions around the country in 2019, according to its website. The headquarters draws thousands of volunteers and visitors each year, and in 2019 the nonprofit received $101 million in donations. It is perhaps best known for taking in 22 of former NFL star Michael Vick’s fighting dogs and for being featured in the National Geographic show “DogTown.”

The group’s website briefly mentions the “Process Church,” but there’s no mention of Satan or the end of the world. Instead, the website describes the founders as friends who were on a spiritual quest to create a better world but eventually grew tired “of complicated cosmologies that added nothing to the preferred simplicity of a life based on service and the Universal Law.”

A woman interacts with puppies in a March 2020 livestreamed video from Best Friends Animal Sanctuary in Kanab, Utah. Video screengrab

Eric C. Rayvid, public relations director of Best Friends Animal Society, said the group is focused on the future, not the past. He had no comment about Jared Garrett’s podcast and the claims that children in the groups were mistreated.

“Any previous affiliations from some of the founders have no bearing on the organization today and is really irrelevant to the work we’re doing around the country to help save dogs and cats in shelters simply because they don’t have a safe place to call home,” Rayvid said in an email.

Bruce Garrett would eventually leave the sect in the early 1990s, after marrying someone outside the group. Now, he is a nurse manager at several clinics in Salt Lake City, having gone to nursing school in his 40s.

He has no ties to organized religion but still considers himself spiritual. Since leaving the sect, he’s worked hard to heal the past rift with his son.

“It’s a work in progress,” he said. “Family is now my priority.”

Jared Garrett’s relationship with his mother, who died of cancer in 1999, was complicated. For much of his early childhood, he only spoke to her twice a year.

As a teenager, he spent summers with her in Utah, working at the budding animal shelter in Kanab, building enclosures for rescued animals and shoveling a few “tons of dog poop,” he said.

Once in a while, he said, he and his mother, who went by the name “Magdelene,” would have lunch at a local Chinese restaurant and talk about their shared love of Stephen King novels. But her past remained a mystery.

Jared Garrett at the age of 14. Courtesy photo

By the time he was 16 and living in Dallas, he planned his escape, hoping to follow in the footsteps of his older brother, who ran away when he was 16. Before he could put his plan into action, the Dallas branch rebelled. Some members quit. Before long, all the remaining members across the country moved to Utah.

Jared’s mom called and offered him a choice. He could move to headquarters permanently or he could move in with his father for his last year of high school. He chose his dad and left the sect for good. His mother remained a devoted member of the Process until her death.

“I won’t question her love for me. I will question her choices,” he said.

When he left, Jared Garrett was sure of one thing. He was done with religion. God made no sense to him.

“The God that was preached to me was a capricious angry God who didn’t really like people very much,” he said. “I just couldn’t buy it.”

After high school, he got a job and got an apartment with some friends. As they were moving in, some missionaries from the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints stopped by. He agreed to study with them but was skeptical at first.

“I didn’t really care for any of it,” he said. “It was all kind of boring. It was religion and I didn’t want religion.”

The sense of welcome and community he found in the church, however, pulled him in. It was not the unstable community he’d grown up in, where he was never sure who could be trusted and there was a God who didn’t have much time for him; instead, this was a place where God liked him and so did the people.

“When I walked into the church for the first time, here comes this tall, former lumberjack. He had a big smile on his face and he said, ‘Jared, we are so glad you’re here,’” Garrett recalled. “And he shakes my hand and puts a warm hand on my shoulder. That’s the first positive touch I’d gotten from a dude ever in my life. And I was like, wow.”

RELATED: Hare Krishnas lift the lid on history of child abuse

Annemarie and Jared Garrett with their family. Photo by Camera Shy Lehi

Returning from his mission, he went to Brigham Young University, where he met his wife, Annemarie. He recently quit his job as an instructional designer to be a stay-at-home dad. He writes novels, including one called “Beyond the Cabin,” a fictionalized account of his departure from the sect. He’s also busy with his volunteer role as a bishop.

Recording the podcast has helped him make sense of his past and reach a point of being able to forgive leaders of the sect. He is about to record a final episode at Best Friends in Kanab.

Jared Garrett supports the pet rescue work the group does, and he’s glad that the sect has found a way to do good work in the world, which he believes is the true meaning of spirituality.

“The number of animals they’ve rescued and rehabilitated is astonishing,” he said.

Still, he wishes the sect would apologize for its past beliefs and for how children were treated, instead of pretending they don’t exist.

“I lie to myself and say that I don’t need (them) to, publicly or privately to me and the other kids, acknowledge that (they) gave birth to and raised us in a terrible environment,” he said in a podcast episode. “I do need to hear that on a deep level.”

Meanwhile, in small, steady ways, he believes he is making the world a better place by paying attention to the things that the sect ignored in its rush to change society.

“I am changing the world,” he said. “Because I have an amazing family and amazing kids and I have changed my own life for the better.”